Turtle Bay History

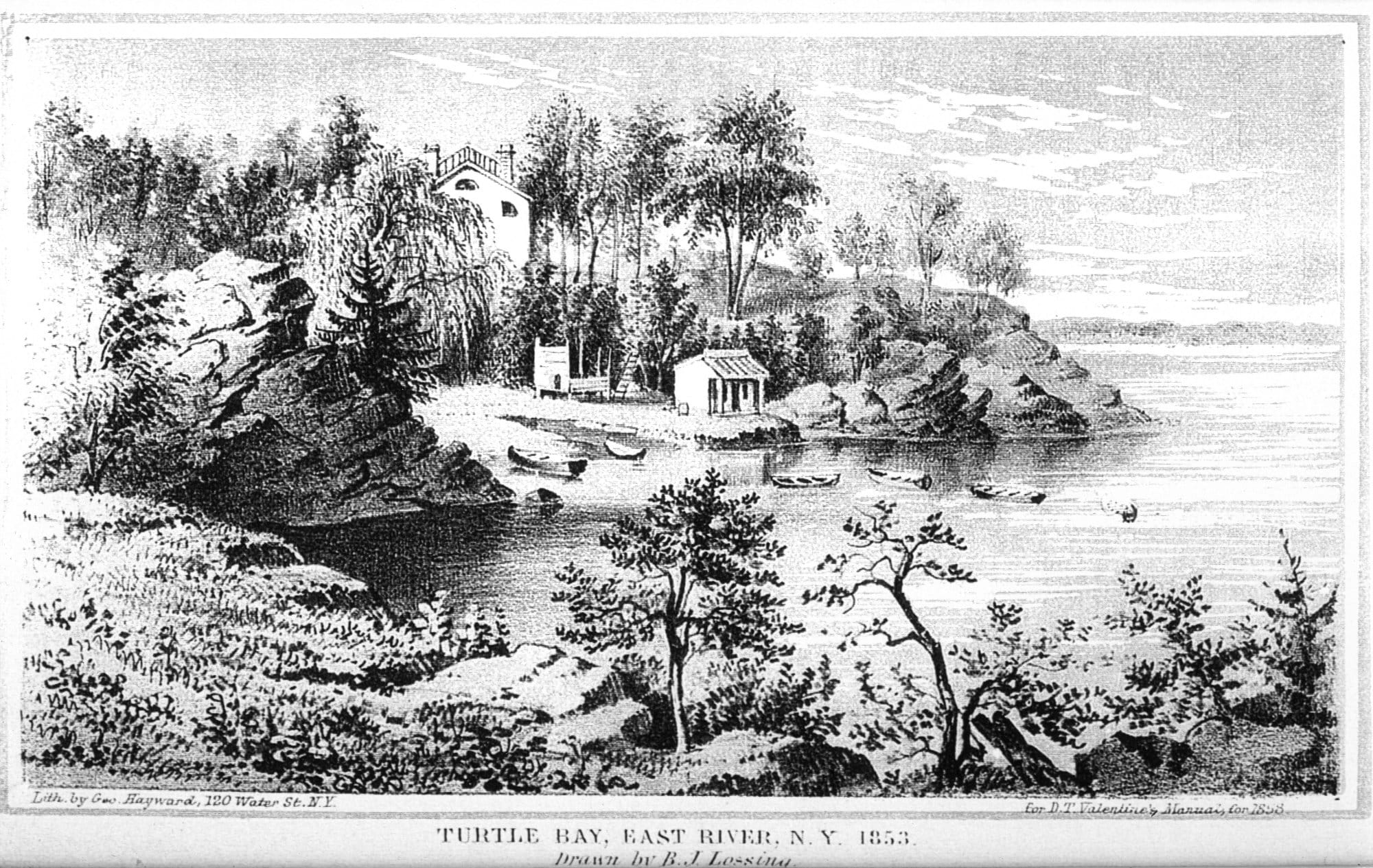

The neighborhood of Turtle Bay is named for a small crescent-shaped cove, called Turtle Bay, that once ran from today’s 45th Street to approximately 48th Street. A meandering stream, called Turtle Creek, flowed southeasterly, emptying into the bay at the foot of what is now 47th Street.

Over the years, the area has continually been transformed – from a pastoral setting of wealthy farms in the 1700s, to a neighborhood of handsome brownstone row houses in the mid-1800s, and then a period of decline in the late 1800s that was reversed with the introduction of some innovative and fashionable residences in the 1920s. Since the late 1940s, Turtle Bay has been home to the United Nations, and has seen numerous high-rise office towers built along Third Avenue, with new luxury apartment towers lining much of First Avenue.

Early Days

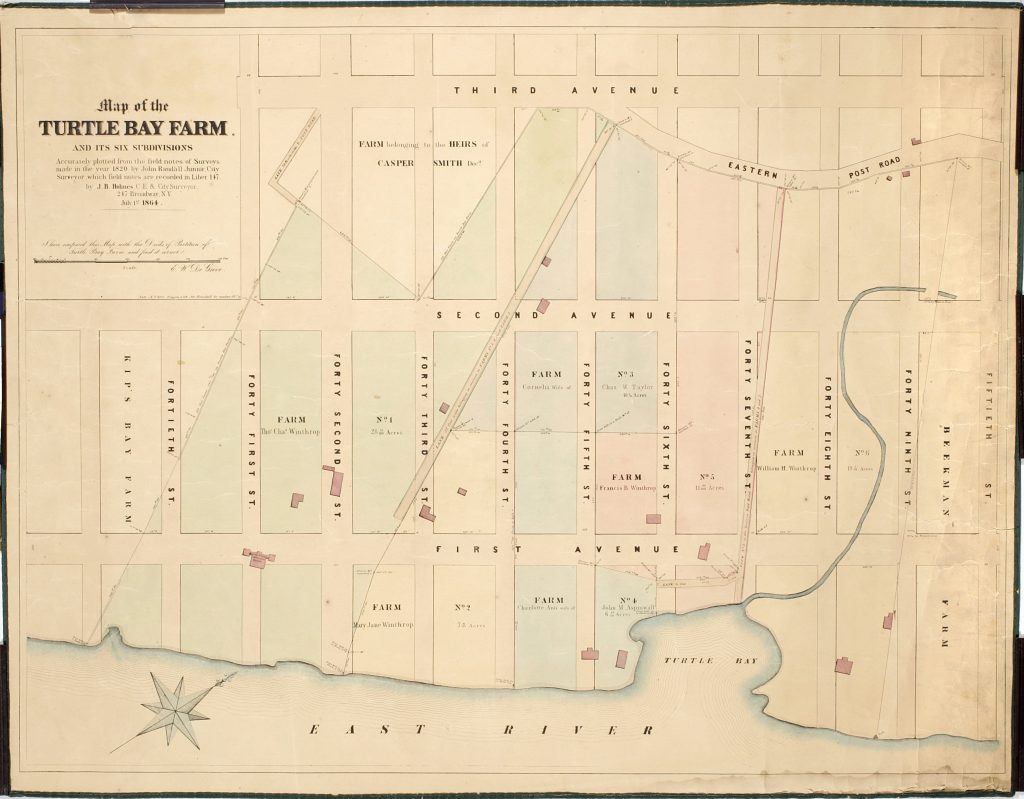

In the 1700s, big farms and estates dotted the area, dominated by two large farms –Turtle Bay Farm, which ran along the East River from 41st Street to 49th Street, and just to the north, the Beekman Farm. Their westerly border was the famous Eastern Post Road, which approximately ran along what today is Third Avenue.

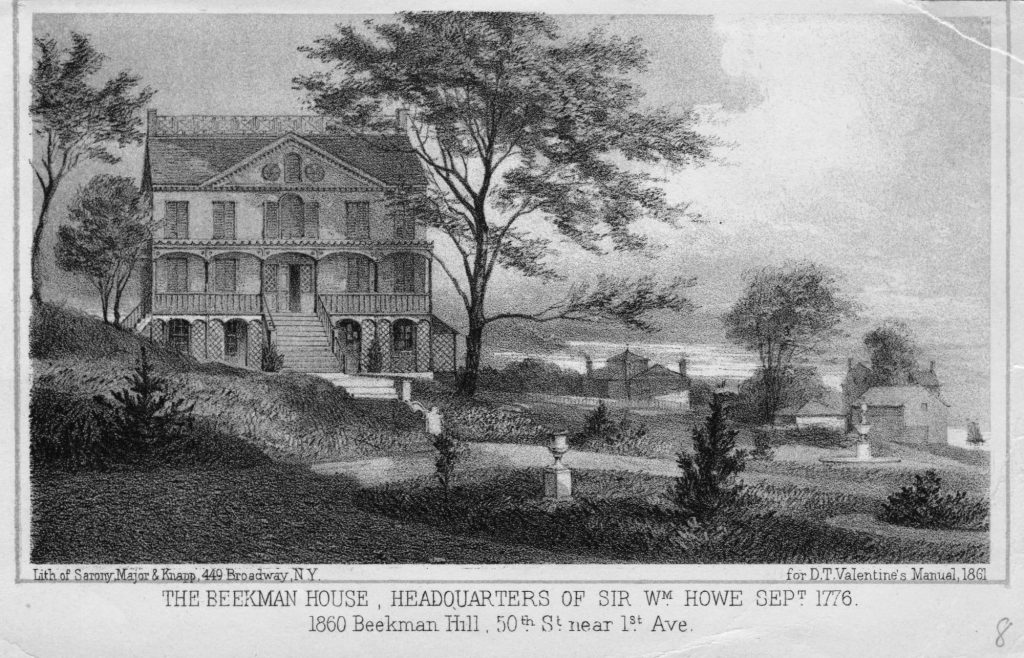

In the 1760s, one of New York City’s most magnificent mansions, called Mount Pleasant, was built by James Beekman on his Beekman Farm property. It stood on high ground at what today is approximately the intersection of First Avenue and 51st Street. The house gained notoriety during the Revolutionary War, when it was taken over by the British and used as a command post. Nathan Hale, the patriot spy, was tried and sentenced to death in the greenhouse on the grounds. The mansion was later demolished to make way for construction of New York City’s street grid.

Farmland to City Streets

In the 1800s, the city limits were pushing northward from lower Manhattan, and the city laid out its straight-line street grid for the future. Gradually, new streets and avenues opened up, reaching the Turtle Bay area by mid-century. The rolling farmland was broken up into building lots, and brownstone row houses began to rise in the area.

Construction slowed during the Civil War but resumed again in the late 1800s. By then, the street building in the area had caused the little Turtle Creek to back up, and the surrounding land became swampy and the water unhealthy. The bay was filled in and an underground drainage system was built, emptying into the East River at about 49th Street.

Soon, the new landfill – the grounds where the United Nations now stands – became an industrial site, taken over by stockyards, slaughterhouses, breweries, and a coal yard. Next, elevated rail lines were built over Second and Third Avenues, turning the two central routes into dark, dirty roadways. Tawdry tenements and rooming houses replaced the area’s one-family brownstones, and by the end of the 19th century, the neighborhood had entered a long period of decline.

Rebirth in the 1920s

The early 1920s brought a renaissance to the area, when a wealthy and creative woman, Charlotte Martin, bought a group of 20 brownstones on 48th and 49th Streets, between Second and Third Avenues, and converted them into charming town houses around a central Italian-inspired garden. Called Turtle Bay Gardens, the houses were highly acclaimed and almost immediately attracted prominent and celebrated residents.

Nearby Beekman Place, which runs from 49th to 51st Streets along the East River, also saw a rebirth when the noted landscape architect Ellen Biddle Shipman started a trend with conversion of an old brownstone into a Georgian-style home.

Soon, the neighborhood of Turtle Bay had become home to some of the most famous theatrical, musical and literary names of the time. In 1932, the actress Katharine Hepburn moved to Turtle Bay Gardens, to a house she owned until her death in 2003. Among others who called the Gardens home in those years were essayist E.B. White, journalist Dorothy Thompson and actress Mary Martin. The writer Thomas Wolfe lived nearby, and later, in the 1940s, the songwriter Irving Berlin bought a house on Beekman Place, where he lived for more than 40 years.

Meanwhile, helping to spur development in Turtle Bay was the demolition of the Second Avenue elevated rail line in 1942, followed by the Third Avenue El some years later. They were the last operating Els in New York City, and for years, they had served as a kind of barrier that kept East Midtown separated from the rest of Manhattan.

The United Nations Marks a Change

Still, the factories and slaughterhouses remained on the landfill on the banks of the East River well into the 1940s. But that changed suddenly in December 1946, when John D. Rockefeller Jr. purchased six blocks of river frontage and donated it to the newly formed United Nations for its headquarters complex. Completed a few years later, the U.N. complex of buildings became among the most architecturally influential in the world, and its landscaped gardens a stark contrast to the industrial structures that had stood on the land for years. The tallest of the buildings, the 37-story Secretariat building, was the first building in New York to use a façade of glazed glass.

New Residential Development

In the 1960s, development of many new high-rise apartment buildings marked a significant change for the area. Among the first and most highly regarded were two twin towers at 49th Street and First Avenue, 860-870 United Nations Plaza, designed by Wallace Harrison, who had been the lead architect of the UN buildings. Decades later, another wave of apartment tower construction saw new modern high rises along First Avenue, including the Trump World Tower, designed by Costas Kondylis, and 50 United Nations Plaza, designed by the highly regarded architect Norman Foster.

Parks and Playgrounds

Over the years, it has been recognized that the neighborhood of Turtle Bay lacked adequate park and playground space, and so neighbors were pleased when, in the mid-1990s, the Turtle Bay Association spearheaded a move to extensively renovate Dag Hammarskjold Plaza, a block-long stretch of land along 47th Street between First and Second avenues. While the neighborhood has other green spaces – among them, Peter Detmold Park, Douglas MacArthur Park, and Greenacre Park – Dag Hammarskjold Plaza has served as the centerpiece of the neighborhood since its reopening in 1999.

Today, as it has since its founding in 1957, the Turtle Bay Association continues to work to maintain the area’s special historic character, and to make Turtle Bay a better place to live and work.

By Pamela Hanlon